I adapted this idea from Sarah Stremming’s “Four Steps to Behavioral Wellness.” These are baseline needs that we must meet for our dogs before we can expect training to have any significant effect on their behavior. Sometimes addressing these needs is in fact all you need to remove problematic behaviors.

Exercise

Ever heard the phrase “a tired dog is a good dog”? While physical exercise won’t solve anxiety issues like separation anxiety, it has a huge impact on nuisance behaviors like jumping and pulling and barking. Any time you are asking your dog to exhibit self control in exciting situations, you must also be providing an appropriate outlet for their energy - they can’t just tamp all of it down without it spilling over in other contexts. Here is an article with all kinds of ideas for providing your dog with physical exercise.

Enrichment

Enrichment refers to activities your dog can engage in that provide mental exercise and entertainment. This is particularly important for “busy” dogs who get into trouble when bored. This is just as important as physical exercise, especially if there are long periods of time that your dog is being asked to just chill at home. The best enrichment strategies for any particular dog are usually ones that enable him to express his natural “doggy” behaviors in an appropriate way. Here is an article with all kinds of ideas for providing your dog with mental enrichment.

Health

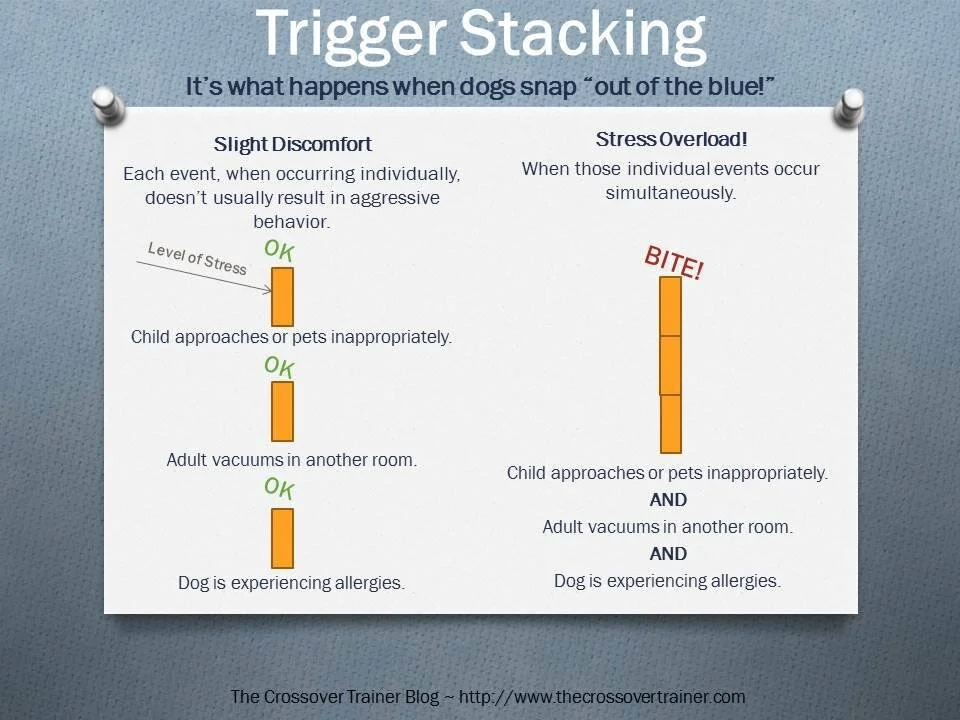

Improper diet, gastrointestinal inflammation and other metabolic diseases, joint pain, sprained muscles, and many other health problems can cause dogs to be irritable, aggressive, anxious, impulsive, or non-responsive to training/“stubborn.” There is even a study linking noise sensitivities with pain in dogs. Think about how hard it is to focus on work when you have a headache, or have patience with your toddler climbing all over you when you’re experiencing back pain, or drive safely when you’re exhausted. These are some of the areas we want to look at when it comes to making sure that our dogs are in good health:

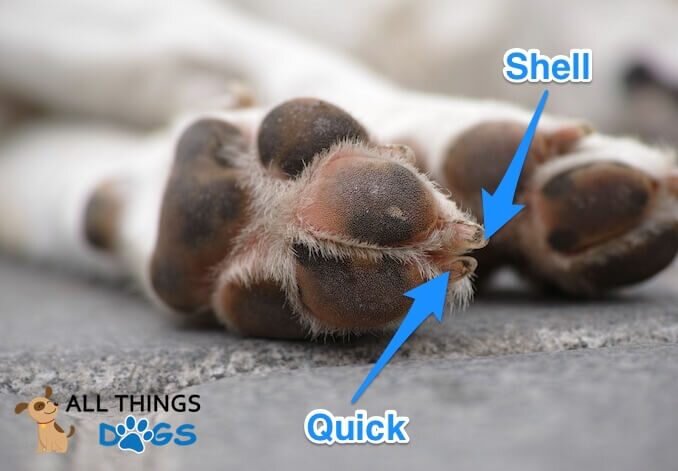

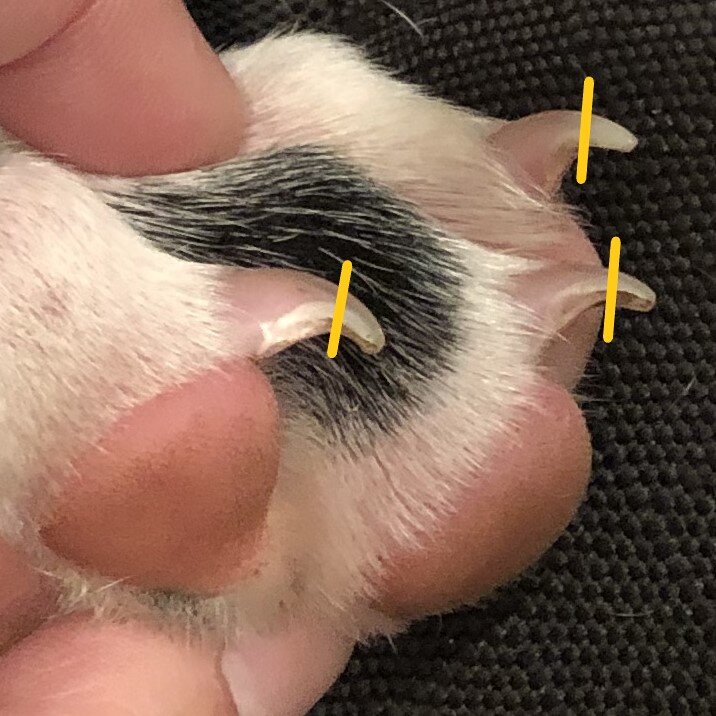

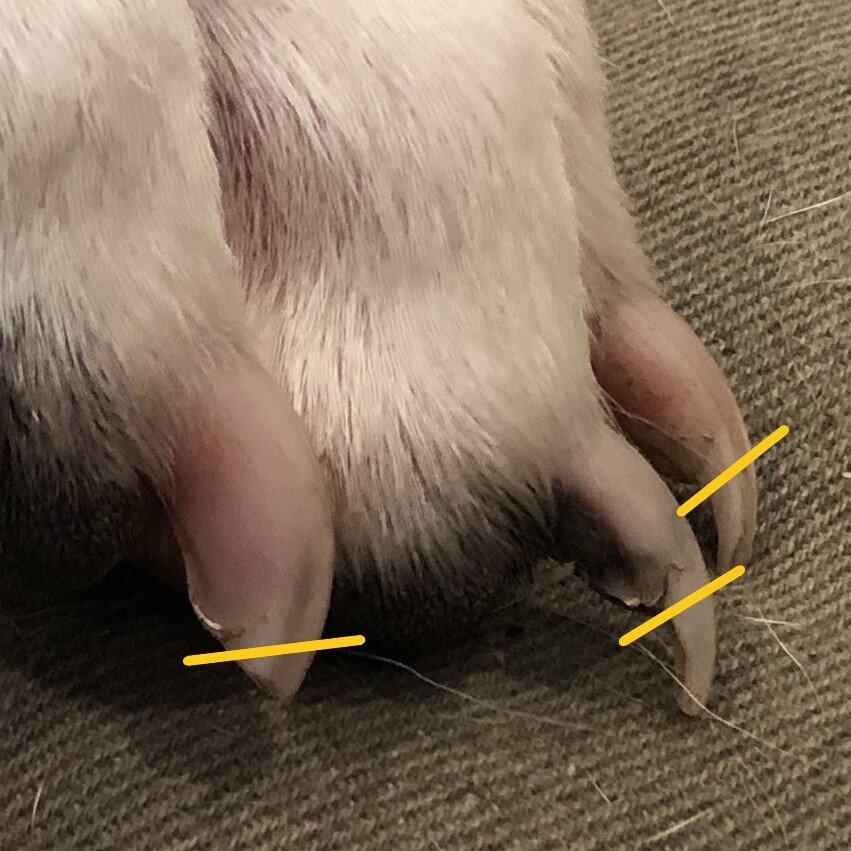

Pain: A comprehensive pain examination by your vet can bring injuries to light or rule them out. In some cases, an appointment with a specialist such as a neurologist may be warranted. You can also empower yourself to watch for injuries by watching (or even video taping) your dog’s walking and trotting gaits, doing gentle stretches, and teaching tricks that have your dog moving in a variety of ways. Watch for imbalances between left and right, changes in willingness to perform a trick, and other differences in movement. Don’t write off intermittent limps or skips in your dog’s steps. If pain is suspected but can’t be pinned down, ask your vet about trying a test course of pain medication. If your dog’s behavior improves on the meds and regresses when taken off, you know that you need to dig further. Furthermore, “If the first analgesia trial does not provide results, it is appropriate to try another type of analgesic with a different mechanism of action, in case the first was not right for that dog’s particular issue. Mills argues that the risk of side effects can be minimized and that the benefits of using pain medication will normally outweigh the risks.”

X-rays: These may reveal arthritis, joint problems (such as hip dysplasia), or other hidden reasons for pain that causes irritability, aggression, or reluctance to perform certain behaviors.

Blood work: A full chemistry profile and complete blood count (CBC) may reveal underlying health conditions that were not yet showing obvious symptoms to the owner, but were felt by the dog and affecting his behavior. For example, aggression is a known possible side effect of hypothyroidism, while decreased functionality of other organs may present as “stubbornness” or anxiety because the dog isn’t feeling well.

Urinary analysis: Any sudden changes in potty training for an adult dog should be followed by a urinary analysis. Some puppies that are particularly difficult to potty train may have UTIs.

Dental cleaning: Jaw and tooth pain may be difficult for a pet owner to diagnose, but be causing reluctance to eat or sensitivity to handling around the head/neck. Keep up with brushing your dog’s teeth and dental cleaning per your vet’s recommendations. Beware of anesthesia-free dental cleanings.

Diet & GI health: Proper canine diets are a controversial subject. I personally have fed my own dogs everything ranging from premade raw food, homemade raw food, premade cooked and frozen food, to grain-free kibble as well as kibble containing grains like wheat. There is a lot of science that has been done on canine nutrition and foods , yet a LOT that still needs to be done. Personally, rather than obsessing over finding just the right foods, I choose to frequently switch up my dogs’ diets - allowing variety to hopefully make up for the deficiencies of any one type. By switching around, you may notice patterns such as your dog getting ear infections or itchy skin on ingredient X, or seemingly random bouts of diarrhea on food Y, or more impulsive behavior or irritability caused by inflammation with product Z.

Sleep: If you’re staying home with busy kids or leaving your dog in the backyard during the day, he may be missing out on needed sleep. Just like humans, dogs benefit from having quiet, dark areas to nap in as needed, and will be cranky and unfocused if sleep deprived. This is especially important for puppies, who famously get “bitey” when overly tired. Puppies typically need 18-20 hours of sleep a day, while adults spend roughly 50% of the day in deep sleep and 30% awake but resting. (See this post on puppy schedules.)

Anxiolytic Medication: For dogs with severe anxiety issues, anxiolytic meds are a game changer. Just like you wouldn’t withhold medication for pain or a liver problem because you expect the dog to “get over it,” providing medication for severe anxiety or aggression is the humane thing to do. Sometimes brains need just as much help as broken bones or infected scratches.

If you suspect that something is physically wrong but your vet cannot find an obvious cause during a physical examination, don’t give up! Sometimes it can take some digging (see this post and comments below for many examples), but there is evidence that “a conservative estimate of around a third of referred [behavior problem] cases involve some form of painful condition, and in some instances, the figure may be nearly 80%.”

Communication

Clear communication is definitely a prerequisite for training. Mixed signals - such as sometimes petting your dog when he puts his paws up, while other times yelling at him because you’re wearing your “nice” clothes - will confuse your dog and grind training progress to a halt. Some aspects of clear communication are:

Consistency: All members of the household should follow the same rules and training procedures, unless there is a specific reason to alter them (for example, young kids may not be able to follow some of the more nuanced training procedures, so are given simplified directions). In addition, each person should make sure that they are consistent throughout the day.

Clear cues: One word/phrase per behavior.

Don’t use the same word to mean different things (such as saying “down” when you want your dog to get off the couch and when you want him to lie down on the floor).

Don’t use multiple words to mean the same thing (such as “shake” and “gimme your paw” for the same action).

Keep your tone consistent (say “come” the same way every time, not sometimes high-pitched and happy and other times low and upset).

Don’t jerk on your dog’s leash when you want him to do something; many owners will jerk when they want their dog to sit, or to slow down, or to stop sniffing, or to look up. How is your dog to know which one you want? Give them a verbal cue or hand signal that has been trained for a specific behavior, instead.

Reward markers: Use a clicker or other quick reward marker to let your dog know when they’ve done something good and earned a reward. I use a happy “yes!” when I want to use a verbal marker instead of a clicker. The reward marker should always be followed by a treat or other reward.

For more information on clicker training, check out Clicker Training 101: A Quick Beginner’s Guide and Frequently Asked Questions about Clicker Training.

Communication goes both ways - in addition to being clear when cuing your dog, you should learn to read his body language so that you can understand what he is “saying” to you. Here are some resources on dog body language.

As we work together to train your dog using humane and effective positive methods, your ability to communicate with your dog will grow exponentially - leading to a stronger bond and more reliable behaviors.